You Only Have 3 Seconds

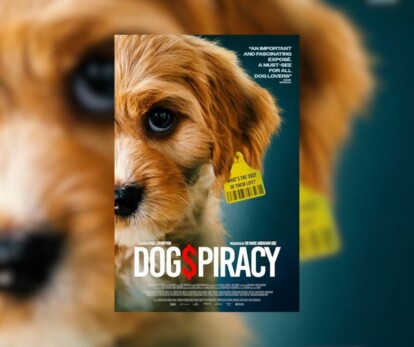

A new documentary premiered at the Phoenix Cinema in London on Tuesday, 22nd July and will be screened at various UK cinemas this summer. We urge you to watch it if you can – we have!

Dogspiracy follows English veterinarian, Marc Abraham OBE, as he campaigns to end the practice of breeding, buying, and selling dogs as part of a global puppy trade. The film promises to pull back the curtain on the multi-billion-dollar industry that fuels puppy mills, online scams, and illegal trafficking, with a particular focus on the UK and US.

If you’ve ever clicked on a “puppy for sale” ad or even cooed over a friend’s new dog, then this issue touches you. Sadly, behind every fluffy face, there might be a story that began in a cage.

The puppy trade is big business. In the EU alone, it’s estimated to be worth over €1.3 billion a year.

Around 8 million dogs are sold annually (again, this is just in the EU; the global figures are unknown), with many of those sales taking place online. Often, there is no way of knowing who’s behind the sales or what the conditions were like for the dogs involved.

In published figures from Scotland, the puppy trade is estimated to be worth around £13 million annually. Some puppy breeds are sold for as much as £2,500 per dog, making breeding a potentially lucrative source of income, especially when it’s estimated that each breeding female has an average of 9.4 puppies per year.

Dogspiracy doesn’t just highlight numbers and the unimaginable scale of the puppy mill industry. It also shows us how this cruel industry impacts the individual dogs existing within it – the mothers forced to breed over and over again in filthy, overcrowded sheds; the puppies who never see daylight; the ones who don’t make it to market; and the ones who do, only to carry trauma, illness, or genetic disorders for the rest of their lives.

The term “puppy mill” might sound old-fashioned or like something that only happens far away. However, these operations, legal or illegal, are very much alive and thriving across the UK, the US, and Europe.

They’re often hidden behind respectable-looking websites, glossy photos, and words like “home-raised” or “KC-registered”, but if you scratch the surface, you find animals treated not as family but as factory output.

The puppy trade causes immense suffering.

The Veterinary Medical Association of the Humane Society of the United States defines the main characteristics of a puppy mill as an “emphasis on quantity over quality, indiscriminate breeding, continuous confinement, lack of human contact and environmental enrichment, poor husbandry, and minimal to no veterinary care”.

In large-scale breeding operations, dogs are routinely kept in cramped, dirty conditions. They’re denied the chance to run, play, sniff, explore, or form healthy bonds. Many are bred repeatedly with no regard for their physical or emotional well-being. When their bodies give out or they’re no longer “useful” (i.e. fertile), they may be sold off, abandoned, or killed.

But the harm doesn’t stop there.

Many of the puppies sold through this system carry the trauma of poor socialisation and early separation from their mothers. This may affect their future behaviour and mental wellbeing. They may also suffer from serious, lifelong physical health problems linked to irresponsible breeding.

Some of the most popular “trend breeds” – chosen for their appearance, social media status, or because they featured in the latest big TV programme or film – are among the most vulnerable. Think of bulldogs who can’t breathe properly, dachshunds with spinal issues, or Dalmatians with a high risk of deafness due to the genetics that make their coats so distinctive.

Even when the breeders are licensed and the surroundings look clean, the push to meet market demand often means that welfare takes a back seat. Dogs are bred to meet consumer tastes rather than for robust health or temperament.

And when demand shifts, dogs suffer again. We’ve seen it time and time again with pugs, cavapoos, French bulldogs, and most recently, XL bullies (the article we’ve linked to was written before the UK’s XL Bully ban, but makes some important points about how irresponsible human intervention can influence temperament and behaviour).

There’s also a loss, harder to pin down but no less real, in the way our culture has normalised the idea that dogs can be bought, owned, and bred to suit human preferences.

Even our language – “pet ownership,” “buying a dog,” “designer breeds” – reflects this commodification.

It’s truly shocking to realise that certain breeds (French bulldogs, English Bulldogs, and Chihuahuas, for example) are so anatomically different due to selective breeding that up to 80% struggle to give birth naturally.

This is just one example of how deeply harmful it can be when breeding is driven by appearance, profit, or popularity rather than the health and dignity of the dogs themselves.

This harm doesn’t happen in isolation. It’s made possible by a system and a society which reward the supply because there’s steady demand. That longing so many of us feel for a particular kind of dog, or the dream of finding “the perfect puppy,” is understandable, but it comes with responsibility.

If we care about dogs, then we must be willing to ask tough questions, not just about where puppies come from, but about whether bringing one home might unintentionally support an industry built on suffering.

Sometimes, loving dogs means being willing to wait. To adopt, not shop. To sit with the discomfort of doing what’s right, even when it means letting go of what we thought we wanted.

Because when we view dogs as kin, not commodities, the true cost of this system becomes clear.

Before we explore what the law says about puppy mills and the wider industry, there’s something else we need to confront: the cruelty of the puppy trade isn’t just about where dogs come from, it’s also about where they end up.

In the US alone, two million dogs are bred in puppy mills each year, while more than 1.2 million are euthanised in shelters. It’s the same in other countries. Rescue organisations are quite literally full. In the UK, 21 healthy dogs are killed every day, simply because there isn’t anywhere to house them.

This isn’t just a supply problem, it’s a values problem.

We’ve created an industry that treats dogs as disposable products: breed them, sell them, replace them. And the ones who don’t fit the mould? They’re left behind, often killed to make room for more.

If we want a world that truly values the lives of our fellow animals, we must reckon with this contradiction. Choosing to buy a dog while others are dying in shelters isn’t a neutral act; it supports a system built on excess, demand, and disregard.

One of the most disturbing things about puppy mills is how often their puppies are sold to well-meaning people who would be horrified to know the truth.

These dogs rarely come with a label that says, “I was bred in a cage”. Instead, the system thrives on manipulation, misdirection, and misplaced but understandable trust.

In the UK, many puppies sold online or through third parties are trafficked from abroad, particularly from countries in Eastern Europe where welfare standards are lower and enforcement is limited.

These puppies are often bred in industrial-scale farms, taken from their mothers far too early, and transported across borders in cramped, filthy vehicles. They arrive under-socialised, sick, and frightened, but come packaged with polished adverts and carefully crafted backstories.

The sellers often appear professional, even compassionate. Some are licensed breeders. Others pose as private individuals with a “surprise litter”. You might see a photo of a puppy nestled beside “mum” in a cosy-looking living room, but that might be a dog placed there to reassure buyers, not the real mother.

And if you ask to meet the mother in person? You might hear:

These are red flags.

So is being asked to meet in a neutral location, such as a car park, a motorway services, or somewhere “convenient”. This tactic is designed to prevent buyers from seeing the true breeding environment.

Even puppies bred in the UK can come from puppy farms hidden behind the façade of a “small family breeder”. High-volume breeders may keep dozens of breeding females in barren kennels, cycling them through litter after litter, with little regard for their health or wellbeing.

Scams are common, too. Some people pay for a puppy they’ve only seen in photos, only to be ghosted. Others bring home a puppy with serious medical issues or undisclosed behavioural challenges.

The trade is built on deception, and it’s alarmingly easy to get caught up in it.

This is why genuine, transparent rescue organisations, or breeders who invite you to meet the mother and see where the puppies live, matter.

But even then, we need to ask the bigger question: are we adding to the demand that keeps this system alive?

In England, a key piece of legislation came into force in April 2020: Lucy’s Law. It was named after Lucy, a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who was rescued from a puppy farm in Wales after years of confinement in a cage, forced breeding, and untreated medical conditions. Her story moved thousands and became the spark behind a campaign that ultimately reached Parliament, led by Dogspiracy’s Marc Abraham OBE.

Lucy’s Law was a significant step in trying to end third-party puppy and kitten sales. It introduced the following key protections:

The aim was to cut out intermediaries and shine a light on the conditions in which dogs and cats were being bred. Campaigners hoped this would stop people from being misled by slick websites or adverts and redirect demand away from cruel puppy farms.

On paper, it was a win. But in practice, many problems remain.

Lucy’s Law applies only in England. It hasn’t been able to stop unlicensed backyard breeding, illegal imports, or online marketplaces that allow unverified sellers to operate freely. Enforcement is patchy, and prosecutions are rare.

Marc Abraham is now campaigning to bring in a similar law in the United States, where regulation is even more limited.

The Animal Welfare Act offers only the most basic protections, and even those are often poorly enforced. Efforts to introduce stronger laws, like the Puppy Protection Act, have so far stalled after facing intense resistance from powerful lobbying groups like the American Kennel Club.

Meanwhile, the EU made headlines in 2023 by proposing sweeping reforms. These were under renewed discussion in June 2025. If adopted, the new legislation would:

The intention is to crack down on illegal trade and increase transparency, potentially striking at the roots of the puppy mill system across Europe.

However, not everyone is convinced.

Several MEPs and animal protection NGOs have raised concerns. Some warn that by framing these changes as trade regulation, the EU risks reinforcing the idea that dogs and cats are commodities, not individuals.

Others point out that exemptions to centralised breeder registries could allow some operations to continue under the radar. There’s also frustration that the reforms don’t go far enough to regulate online sales, which remain a major gateway for illegal trade, and that shelter animals are still insufficiently protected.

Without robust, consistent enforcement across EU member states, campaigners fear these reforms may end up symbolic rather than transformative.

And of course, passing legislation is only the beginning. Political will, adequate funding, enforcement infrastructure, and public support all play a role in deciding whether laws make a real-world difference.

If the harm is so clear, why is it so hard to crack down on puppy mills?

The answer is uncomfortable and often comes down to two key areas: public demand and institutional resistance.

As we’ve already noted, public demand continues to drive the puppy trade.

Many people want specific breeds, often quickly, and without questioning where those dogs have come from. Social media and celebrity culture have played a huge role in shaping trends, fuelling demand for brachycephalic or “fashionable” breeds despite their well-known health issues.

Too often, the focus is on aesthetics rather than well-being. Dogs are bred to look a certain way (shorter noses, smaller bodies, rounder eyes) often because they more closely resemble human infants. But these traits can cause lifelong pain and impair basic functions like breathing, walking, and even giving birth. The result is a steady stream of puppies whose suffering begins before they’re even born.

This is compounded by a lack of public education and transparency. Many buyers don’t realise the puppy they’re bringing home may have come from a high-volume breeder or puppy farm operating behind a slick front.

While online sales remain poorly regulated and our culture continues to treat dogs as “on demand”, the cycle continues.

Campaigners stress that awareness is key. Organisations like the Humane Society of the United States and The Puppy Mill Project have shown that education can shift consumer behaviour, but only if people are willing to confront the uncomfortable realities behind the ads and cute photos.

Public demand isn’t the only reason puppy mills persist. Behind the scenes, industry lobbying and political hesitation play a powerful role.

In the US, the American Kennel Club (AKC) has repeatedly opposed stronger breeding regulations, including the Puppy Protection Act, while branding itself as a champion of responsible dog ownership.

A large portion of the AKC’s funding comes from dog registrations and breeder events, creating a clear financial incentive to resist reforms that would limit or regulate breeding.

In the UK, the Kennel Club also earns income from breed registrations, dog shows, and breeder schemes. While it promotes welfare guidance and has supported initiatives like Puppy Awareness Week, it has also been criticised for defending breed standards that contribute to severe health problems.

Critics argue that its reluctance to reform these standards enables harmful practices to continue under the banner of tradition and prestige.

Across the EU, as we explored earlier, recent reform proposals aim to introduce greater oversight and traceability. But even if those rules are adopted, their effectiveness will depend on how they’re implemented across different countries – and that’s where the political dynamics become even more complicated.

Each EU member state has its own laws, enforcement capacity, and cultural attitudes toward dogs. These differences can make negotiation difficult and meaningful oversight uneven. For example, while some countries prioritise community care, neuter-and-release programmes, and adoption, others still rely on culling or long-term detention of stray dogs.

These variations reflect how dogs are viewed, either as individuals deserving protection, or as problems to be managed. A worldview that treats dogs as disposable allows puppy mills to persist and makes meaningful reform difficult to achieve.

It’s not easy to confront the fact that something as joyful as getting a puppy can be linked to suffering. But once we know the truth, we carry a responsibility to do better.

Here are some starting points:

If 1.2 million individuals (and remember, that’s just in the US, not worldwide!) are killed each year because they’re unwanted, is it right to bring even more dogs into the world?

Some argue that ethical breeding can support health and temperament, but the reality is that every bred litter potentially displaces a dog in need of a home and keeps the broader trade alive. If we want to reduce harm, we need to ask difficult questions about the necessity of breeding at all.

Justice for dogs can’t be separated from justice for all animals.

Puppy mills are just one symptom of a much wider issue: the human belief that we can breed, buy, and control other lives for our own ends. Regardless of species, the root problem is the same, a worldview that places human desires above non-human rights.

Domestication itself raises complex questions. Many dogs today exist only because we created them through generations of selective breeding, often with little regard for their physical or emotional needs. As we move toward a more ethical future, we must ask what kind of relationships we want to have with our animal kin, and what responsibilities we carry.

Dogspiracy may shock and upset people, but if it opens our eyes to what’s happening, and what’s possible, then it’s done its job.

Let’s not look away. Let’s speak up, act, and be the best friends and guardians that dogs and other animals deserve.

A new documentary premiered at the Phoenix Cinema in London on Tuesday 22nd July and will be screened at various UK cinemas this summer. We urge you to watch it if you can – we certainly will!

Dogspiracy follows English veterinarian, Marc Abraham, as he campaigns to end the practice of breeding, buying, and selling dogs as part of a global puppy trade. The film promises to pull back the curtain on the multi-billion-dollar industry that fuels puppy mills, online scams, and illegal trafficking, with a particular focus on the UK and US.

If you’ve ever clicked on a “puppy for sale” ad or even cooed over a friend’s new dog, then this issue touches you. Sadly, behind every fluffy face, there might be a story that began in a cage.

The puppy trade is big business. In the EU alone, it’s estimated to be worth over €1.3 billion a year.

Around 8 million dogs are sold annually (again, this is just in the EU; the global figures are unknown) with many of those sales taking place online. Often, there is no way of knowing who’s behind the sales or what the conditions were like for the dogs involved.

In published figures from Scotland, the puppy trade is estimated to be worth around £13 million annually. Some puppy breeds are sold for as much as £2,500 per dog, making breeding a potentially lucrative source of income, especially when it’s estimated that each breeding female has an average of 9.4 puppies per year.

Dogspiracy doesn’t just highlight numbers and the unimaginable scale of the puppy mill industry. It also shows us how this cruel industry impacts the individual dogs existing within it – the mothers forced to breed over and over again in filthy, overcrowded sheds; the puppies who never see daylight; the ones who don’t make it to market; and the ones who do, only to carry trauma, illness, or genetic disorders for the rest of their lives.

The term “puppy mill” might sound old-fashioned or like something that only happens far away. However, these operations, legal or illegal, are very much alive and thriving across the UK, US, and Europe.

They’re often hidden behind respectable-looking websites, glossy photos, and words like “home-raised” or “KC-registered”, but if you scratch the surface, you find animals treated not as family but as factory output.

The puppy trade causes immense suffering.

The Veterinary Medical Association of the Humane Society of the United States defines the main characteristics of a puppy mill as an “emphasis on quantity over quality, indiscriminate breeding, continuous confinement, lack of human contact and environmental enrichment, poor husbandry, and minimal to no veterinary care”.

In large-scale breeding operations, dogs are routinely kept in cramped, dirty conditions. They’re denied the chance to run, play, sniff, explore, or form healthy bonds. Many are bred repeatedly with no regard for their physical or emotional well-being. When their bodies give out or they’re no longer “useful” (i.e. fertile), they may be sold off, abandoned, or killed.

But the harm doesn’t stop there.

Many of the puppies sold through this system carry the trauma of poor socialisation and early separation from their mothers. This may affect their future behaviour and mental wellbeing. They may also suffer from serious, lifelong physical health problems linked to irresponsible breeding.

Some of the most popular “trend breeds” – chosen for their appearance, social media status, or because they featured in the latest big TV programme or film – are among the most vulnerable. Think of bulldogs who can’t breathe properly, dachshunds with spinal issues, or Dalmatians with a high risk of deafness due to the genetics that make their coats so distinctive.

Even when the breeders are licensed and the surroundings look clean, the push to meet market demand often means that welfare takes a back seat. Dogs are bred to meet consumer tastes rather than for robust health or temperament.

And when demand shifts, dogs suffer again. We’ve seen it time and time again with pugs, cavapoos, French bulldogs, and most recently, XL bullies (the article we’ve linked to was written before the UK’s XL Bully ban, but makes some important points about how irresponsible human intervention can influence temperament and behaviour).

There’s also a loss, harder to pin down but no less real, in the way our culture has normalised the idea that dogs can be bought, owned, and bred to suit human preferences.

Even our language – “pet ownership,” “buying a dog,” “designer breeds” – reflects this commodification.

It’s truly shocking to realise that certain breeds (French bulldogs, English Bulldogs, and Chihuahuas, for example) are so anatomically different due to selective breeding that up to 80% struggle to give birth naturally.

This is just one example of how deeply harmful it can be when breeding is driven by appearance, profit, or popularity rather than the health and dignity of the dogs themselves.

This harm doesn’t happen in isolation. It’s made possible by a system, and a society, which rewards the supply because there’s steady demand. That longing so many of us feel for a particular kind of dog, or the dream of finding “the perfect puppy,” is understandable, but it comes with responsibility.

If we care about dogs, then we must be willing to ask tough questions, not just about where puppies come from, but about whether bringing one home might unintentionally support an industry built on suffering.

Sometimes, loving dogs means being willing to wait. To adopt, not shop. To sit with the discomfort of doing what’s right, even when it means letting go of what we thought we wanted.

Because when we view dogs as kin, not commodities, the true cost of this system becomes clear.

Before we explore what the law says about puppy mills and the wider industry, there’s something else we need to confront: the cruelty of the puppy trade isn’t just about where dogs come from, it’s also about where they end up.

In the US alone, two million dogs are bred in puppy mills each year, while more than 1.2 million are euthanised in shelters. It’s the same in other countries. Rescue organisations are quite literally full. In the UK, 21 healthy dogs are killed every day, simply because there isn’t anywhere to house them.

This isn’t just a supply problem, it’s a values problem.

We’ve created an industry that treats dogs as disposable products: breed them, sell them, replace them. And the ones who don’t fit the mould? They’re left behind, often killed to make room for more.

If we want a world that truly values the lives of our fellow animals, we must reckon with this contradiction. Choosing to buy a dog while others are dying in shelters isn’t a neutral act; it supports a system built on excess, demand, and disregard.

One of the most disturbing things about puppy mills is how often their puppies are sold to well-meaning people who would be horrified to know the truth.

These dogs rarely come with a label that says, “I was bred in a cage”. Instead, the system thrives on manipulation, misdirection, and misplaced but understandable trust.

In the UK, many puppies sold online or through third parties are trafficked from abroad, particularly from countries in Eastern Europe where welfare standards are lower and enforcement is limited.

These puppies are often bred in industrial-scale farms, taken from their mothers far too early, and transported across borders in cramped, filthy vehicles. They arrive under-socialised, sick, and frightened, but come packaged with polished adverts and carefully crafted backstories.

The sellers often appear professional, even compassionate. Some are licensed breeders. Others pose as private individuals with a “surprise litter”. You might see a photo of a puppy nestled beside “mum” in a cosy-looking living room, but that might be a dog placed there to reassure buyers, not the real mother.

And if you ask to meet the mother in person? You might hear:

These are red flags.

So is being asked to meet in a neutral location, such as a car park, a motorway services, or somewhere “convenient”. This tactic is designed to prevent buyers from seeing the true breeding environment.

Even puppies bred in the UK can come from puppy farms hidden behind the façade of a “small family breeder”. High-volume breeders may keep dozens of breeding females in barren kennels, cycling them through litter after litter, with little regard for their health or wellbeing.

Scams are common too. Some people pay for a puppy they’ve only seen in photos, only to be ghosted. Others bring home a puppy with serious medical issues or undisclosed behavioural challenges.

The trade is built on deception, and it’s alarmingly easy to get caught up in it.

This is why genuine, transparent rescue organisations, or breeders who invite you to meet the mother and see where the puppies live, matter.

But even then, we need to ask the bigger question: are we adding to the demand that keeps this system alive?

In England, a key piece of legislation came into force in April 2020: Lucy’s Law. It was named after Lucy, a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who was rescued from a puppy farm in Wales after years of confinement in a cage, forced breeding, and untreated medical conditions. Her story moved thousands and became the spark behind a campaign that ultimately reached Parliament, led by Dogspiracy’s Marc Abraham.

Lucy’s Law was a significant step in trying to end third-party puppy and kitten sales. It introduced the following key protections:

The aim was to cut out intermediaries and shine a light on the conditions dogs and cats were being bred in. Campaigners hoped this would stop people from being misled by slick websites or adverts and redirect demand away from cruel puppy farms.

On paper, it was a win. But in practice, many problems remain.

Lucy’s Law applies only in England. It hasn’t been able to stop unlicensed backyard breeding, illegal imports, or online marketplaces that allow unverified sellers to operate freely. Enforcement is patchy, and prosecutions are rare.

Marc Abraham is now campaigning to bring in a similar law in the United States, where regulation is even more limited.

The Animal Welfare Act offers only the most basic protections, and even those are often poorly enforced. Efforts to introduce stronger laws, like the Puppy Protection Act, have so far stalled after facing intense resistance from powerful lobbying groups like the American Kennel Club.

Meanwhile, the EU made headlines in 2023 by proposing sweeping reforms. These were under renewed discussion in June 2025. If adopted, the new legislation would:

The intention is to crack down on illegal trade and increase transparency, potentially striking at the roots of the puppy mill system across Europe.

However, not everyone is convinced.

Several MEPs and animal protection NGOs have raised concerns. Some warn that by framing these changes as trade regulation, the EU risks reinforcing the idea that dogs and cats are commodities, not individuals.

Others point out that exemptions to centralised breeder registries could allow some operations to continue under the radar. There’s also frustration that the reforms don’t go far enough to regulate online sales, which remain a major gateway for illegal trade, and that shelter animals are still insufficiently protected.

Without robust, consistent enforcement across EU member states, campaigners fear these reforms may end up symbolic rather than transformative.

And of course, passing legislation is only the beginning. Political will, adequate funding, enforcement infrastructure, and public support all play a role in deciding whether laws make a real-world difference.

If the harm is so clear, why is it so hard to crack down on puppy mills?

The answer is uncomfortable and often comes down to two key areas: public demand and institutional resistance.

As we’ve already noted, public demand continues to drive the puppy trade.

Many people want specific breeds, often quickly, and without questioning where those dogs have come from. Social media and celebrity culture have played a huge role in shaping trends, fuelling demand for brachycephalic or “fashionable” breeds despite their well-known health issues.

Too often, the focus is on aesthetics rather than well-being. Dogs are bred to look a certain way (shorter noses, smaller bodies, rounder eyes) often because they more closely resemble human infants. But these traits can cause lifelong pain and impair basic functions like breathing, walking, and even giving birth. The result is a steady stream of puppies whose suffering begins before they’re even born.

This is compounded by a lack of public education and transparency. Many buyers don’t realise the puppy they’re bringing home may have come from a high-volume breeder or puppy farm operating behind a slick front.

While online sales remain poorly regulated and our culture continues to treat dogs as “on demand”, the cycle continues.

Campaigners stress that awareness is key. Organisations like the Humane Society of the United States and The Puppy Mill Project have shown that education can shift consumer behaviour, but only if people are willing to confront the uncomfortable realities behind the ads and cute photos.

Public demand isn’t the only reason puppy mills persist. Behind the scenes, industry lobbying and political hesitation play a powerful role.

In the US, the American Kennel Club (AKC) has repeatedly opposed stronger breeding regulations, including the Puppy Protection Act, while branding itself as a champion of responsible dog ownership.

A large portion of the AKC’s funding comes from dog registrations and breeder events, creating a clear financial incentive to resist reforms that would limit or regulate breeding.

In the UK, the Kennel Club also earns income from breed registrations, dog shows, and breeder schemes. While it promotes welfare guidance and has supported initiatives like Puppy Awareness Week, it has also been criticised for defending breed standards that contribute to severe health problems.

Critics argue that its reluctance to reform these standards enables harmful practices to continue under the banner of tradition and prestige.

Across the EU, as we explored earlier, recent reform proposals aim to introduce greater oversight and traceability. But even if those rules are adopted, their effectiveness will depend on how they’re implemented across different countries – and that’s where the political dynamics become even more complicated.

Each EU member state has its own laws, enforcement capacity, and cultural attitudes toward dogs. These differences can make negotiation difficult and meaningful oversight uneven. For example, while some countries prioritise community care, neuter-and-release programmes, and adoption, others still rely on culling or long-term detention of stray dogs.

These variations reflect how dogs are viewed, either as individuals deserving protection, or as problems to be managed. A worldview that treats dogs as disposable allows puppy mills to persist and makes meaningful reform difficult to achieve.

It’s not easy to confront the fact that something as joyful as getting a puppy can be linked to suffering. But once we know the truth, we carry a responsibility to do better.

Here are some starting points:

If 1.2 million individuals (and remember, that’s just in the US, not worldwide!) are killed each year because they’re unwanted, is it right to bring even more dogs into the world?

Some argue that ethical breeding can support health and temperament, but the reality is that every bred litter potentially displaces a dog in need of a home and keeps the broader trade alive. If we want to reduce harm, we need to ask difficult questions about the necessity of breeding at all.

Justice for dogs can’t be separated from justice for all animals.

Puppy mills are just one symptom of a much wider issue: the human belief that we can breed, buy, and control other lives for our own ends. Regardless of species, the root problem is the same, a worldview that places human desires above non-human rights.

Domestication itself raises complex questions. Many dogs today exist only because we created them through generations of selective breeding, often with little regard for their physical or emotional needs. As we move toward a more ethical future, we must ask what kind of relationships we want to have with our animal kin, and what responsibilities we carry.

Dogspiracy may shock and upset people, but if it opens our eyes to what’s happening, and what’s possible, then it’s done its job.

Let’s not look away. Let’s speak up, act, and be the best friends and guardians that dogs and other animals deserve.

A new documentary premiered at the Phoenix Cinema in London on Tuesday 22nd July and will be screened at various UK cinemas this summer. We urge you to watch it if you can – we certainly will!

Dogspiracy follows English veterinarian, Marc Abraham, as he campaigns to end the practice of breeding, buying, and selling dogs as part of a global puppy trade. The film promises to pull back the curtain on the multi-billion-dollar industry that fuels puppy mills, online scams, and illegal trafficking, with a particular focus on the UK and US.

If you’ve ever clicked on a “puppy for sale” ad or even cooed over a friend’s new dog, then this issue touches you. Sadly, behind every fluffy face, there might be a story that began in a cage.

The puppy trade is big business. In the EU alone, it’s estimated to be worth over €1.3 billion a year.

Around 8 million dogs are sold annually (again, this is just in the EU; the global figures are unknown) with many of those sales taking place online. Often, there is no way of knowing who’s behind the sales or what the conditions were like for the dogs involved.

In published figures from Scotland, the puppy trade is estimated to be worth around £13 million annually. Some puppy breeds are sold for as much as £2,500 per dog, making breeding a potentially lucrative source of income, especially when it’s estimated that each breeding female has an average of 9.4 puppies per year.

Dogspiracy doesn’t just highlight numbers and the unimaginable scale of the puppy mill industry. It also shows us how this cruel industry impacts the individual dogs existing within it – the mothers forced to breed over and over again in filthy, overcrowded sheds; the puppies who never see daylight; the ones who don’t make it to market; and the ones who do, only to carry trauma, illness, or genetic disorders for the rest of their lives.

The term “puppy mill” might sound old-fashioned or like something that only happens far away. However, these operations, legal or illegal, are very much alive and thriving across the UK, US, and Europe.

They’re often hidden behind respectable-looking websites, glossy photos, and words like “home-raised” or “KC-registered”, but if you scratch the surface, you find animals treated not as family but as factory output.

The puppy trade causes immense suffering.

The Veterinary Medical Association of the Humane Society of the United States defines the main characteristics of a puppy mill as an “emphasis on quantity over quality, indiscriminate breeding, continuous confinement, lack of human contact and environmental enrichment, poor husbandry, and minimal to no veterinary care”.

In large-scale breeding operations, dogs are routinely kept in cramped, dirty conditions. They’re denied the chance to run, play, sniff, explore, or form healthy bonds. Many are bred repeatedly with no regard for their physical or emotional well-being. When their bodies give out or they’re no longer “useful” (i.e. fertile), they may be sold off, abandoned, or killed.

But the harm doesn’t stop there.

Many of the puppies sold through this system carry the trauma of poor socialisation and early separation from their mothers. This may affect their future behaviour and mental wellbeing. They may also suffer from serious, lifelong physical health problems linked to irresponsible breeding.

Some of the most popular “trend breeds” – chosen for their appearance, social media status, or because they featured in the latest big TV programme or film – are among the most vulnerable. Think of bulldogs who can’t breathe properly, dachshunds with spinal issues, or Dalmatians with a high risk of deafness due to the genetics that make their coats so distinctive.

Even when the breeders are licensed and the surroundings look clean, the push to meet market demand often means that welfare takes a back seat. Dogs are bred to meet consumer tastes rather than for robust health or temperament.

And when demand shifts, dogs suffer again. We’ve seen it time and time again with pugs, cavapoos, French bulldogs, and most recently, XL bullies (the article we’ve linked to was written before the UK’s XL Bully ban, but makes some important points about how irresponsible human intervention can influence temperament and behaviour).

There’s also a loss, harder to pin down but no less real, in the way our culture has normalised the idea that dogs can be bought, owned, and bred to suit human preferences.

Even our language – “pet ownership,” “buying a dog,” “designer breeds” – reflects this commodification.

It’s truly shocking to realise that certain breeds (French bulldogs, English Bulldogs, and Chihuahuas, for example) are so anatomically different due to selective breeding that up to 80% struggle to give birth naturally.

This is just one example of how deeply harmful it can be when breeding is driven by appearance, profit, or popularity rather than the health and dignity of the dogs themselves.

This harm doesn’t happen in isolation. It’s made possible by a system, and a society, which rewards the supply because there’s steady demand. That longing so many of us feel for a particular kind of dog, or the dream of finding “the perfect puppy,” is understandable, but it comes with responsibility.

If we care about dogs, then we must be willing to ask tough questions, not just about where puppies come from, but about whether bringing one home might unintentionally support an industry built on suffering.

Sometimes, loving dogs means being willing to wait. To adopt, not shop. To sit with the discomfort of doing what’s right, even when it means letting go of what we thought we wanted.

Because when we view dogs as kin, not commodities, the true cost of this system becomes clear.

Before we explore what the law says about puppy mills and the wider industry, there’s something else we need to confront: the cruelty of the puppy trade isn’t just about where dogs come from, it’s also about where they end up.

In the US alone, two million dogs are bred in puppy mills each year, while more than 1.2 million are euthanised in shelters. It’s the same in other countries. Rescue organisations are quite literally full. In the UK, 21 healthy dogs are killed every day, simply because there isn’t anywhere to house them.

This isn’t just a supply problem, it’s a values problem.

We’ve created an industry that treats dogs as disposable products: breed them, sell them, replace them. And the ones who don’t fit the mould? They’re left behind, often killed to make room for more.

If we want a world that truly values the lives of our fellow animals, we must reckon with this contradiction. Choosing to buy a dog while others are dying in shelters isn’t a neutral act; it supports a system built on excess, demand, and disregard.

One of the most disturbing things about puppy mills is how often their puppies are sold to well-meaning people who would be horrified to know the truth.

These dogs rarely come with a label that says, “I was bred in a cage”. Instead, the system thrives on manipulation, misdirection, and misplaced but understandable trust.

In the UK, many puppies sold online or through third parties are trafficked from abroad, particularly from countries in Eastern Europe where welfare standards are lower and enforcement is limited.

These puppies are often bred in industrial-scale farms, taken from their mothers far too early, and transported across borders in cramped, filthy vehicles. They arrive under-socialised, sick, and frightened, but come packaged with polished adverts and carefully crafted backstories.

The sellers often appear professional, even compassionate. Some are licensed breeders. Others pose as private individuals with a “surprise litter”. You might see a photo of a puppy nestled beside “mum” in a cosy-looking living room, but that might be a dog placed there to reassure buyers, not the real mother.

And if you ask to meet the mother in person? You might hear:

These are red flags.

So is being asked to meet in a neutral location, such as a car park, a motorway services, or somewhere “convenient”. This tactic is designed to prevent buyers from seeing the true breeding environment.

Even puppies bred in the UK can come from puppy farms hidden behind the façade of a “small family breeder”. High-volume breeders may keep dozens of breeding females in barren kennels, cycling them through litter after litter, with little regard for their health or wellbeing.

Scams are common too. Some people pay for a puppy they’ve only seen in photos, only to be ghosted. Others bring home a puppy with serious medical issues or undisclosed behavioural challenges.

The trade is built on deception, and it’s alarmingly easy to get caught up in it.

This is why genuine, transparent rescue organisations, or breeders who invite you to meet the mother and see where the puppies live, matter.

But even then, we need to ask the bigger question: are we adding to the demand that keeps this system alive?

In England, a key piece of legislation came into force in April 2020: Lucy’s Law. It was named after Lucy, a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who was rescued from a puppy farm in Wales after years of confinement in a cage, forced breeding, and untreated medical conditions. Her story moved thousands and became the spark behind a campaign that ultimately reached Parliament, led by Dogspiracy’s Marc Abraham.

Lucy’s Law was a significant step in trying to end third-party puppy and kitten sales. It introduced the following key protections:

The aim was to cut out intermediaries and shine a light on the conditions dogs and cats were being bred in. Campaigners hoped this would stop people from being misled by slick websites or adverts and redirect demand away from cruel puppy farms.

On paper, it was a win. But in practice, many problems remain.

Lucy’s Law applies only in England. It hasn’t been able to stop unlicensed backyard breeding, illegal imports, or online marketplaces that allow unverified sellers to operate freely. Enforcement is patchy, and prosecutions are rare.

A major step forward in tackling cruelty linked to puppy mills and illegal pet imports is underway in the UK. The “Animal Welfare (Import of Dogs, Cats and Ferrets) Bill”, brought forward by vet and MP Dr. Danny Chambers, has passed through the House of Commons and is now on its way to the House of Lords. The Bill introduces vital protections, including raising the minimum import age of puppies and kittens to six months, banning the import of heavily pregnant animals, and prohibiting the import of animals with mutilations such as cropped ears or declawed paws. These measures are designed to close the exploitation of legal loopholes by unscrupulous breeders and traders who profit from the suffering of fellow animals.

The Bill also tightens regulations around non-commercial pet travel to stop smugglers posing as holidaymakers. Backed by leading animal welfare organisations and cross-party MPs, this legislation aims to disrupt the supply chain that fuels puppy mills – many of which keep animals in squalid, inhumane conditions. If passed into law, it will help protect thousands of animals from needless suffering while supporting the UK’s reputation as a nation of animal lovers. It’s a long-overdue move to put compassion and welfare before profit.

There are campaigns to bring in a similar law in the United States, where regulation is even more limited.

The Animal Welfare Act offers only the most basic protections, and even those are often poorly enforced. Efforts to introduce stronger laws, like the Puppy Protection Act, have so far stalled after facing intense resistance from powerful lobbying groups like the American Kennel Club.

Meanwhile, the EU made headlines in 2023 by proposing sweeping reforms. These were under renewed discussion in June 2025. If adopted, the new legislation would:

The intention is to crack down on illegal trade and increase transparency, potentially striking at the roots of the puppy mill system across Europe.

However, not everyone is convinced.

Several MEPs and animal protection NGOs have raised concerns. Some warn that by framing these changes as trade regulation, the EU risks reinforcing the idea that dogs and cats are commodities, not individuals.

Others point out that exemptions to centralised breeder registries could allow some operations to continue under the radar. There’s also frustration that the reforms don’t go far enough to regulate online sales, which remain a major gateway for illegal trade, and that shelter animals are still insufficiently protected.

Without robust, consistent enforcement across EU member states, campaigners fear these reforms may end up symbolic rather than transformative.

And of course, passing legislation is only the beginning. Political will, adequate funding, enforcement infrastructure, and public support all play a role in deciding whether laws make a real-world difference.

If the harm is so clear, why is it so hard to crack down on puppy mills?

The answer is uncomfortable and often comes down to two key areas: public demand and institutional resistance.

1. Cultural and consumer resistance

As we’ve already noted, public demand continues to drive the puppy trade.

Many people want specific breeds, often quickly, and without questioning where those dogs have come from. Social media and celebrity culture have played a huge role in shaping trends, fuelling demand for brachycephalic or “fashionable” breeds despite their well-known health issues.

Too often, the focus is on aesthetics rather than well-being. Dogs are bred to look a certain way (shorter noses, smaller bodies, rounder eyes) often because they more closely resemble human infants. But these traits can cause lifelong pain and impair basic functions like breathing, walking, and even giving birth. The result is a steady stream of puppies whose suffering begins before they’re even born.

This is compounded by a lack of public education and transparency. Many buyers don’t realise the puppy they’re bringing home may have come from a high-volume breeder or puppy farm operating behind a slick front.

While online sales remain poorly regulated and our culture continues to treat dogs as “on demand”, the cycle continues.

Campaigners stress that awareness is key. Organisations like the Humane Society of the United States and The Puppy Mill Project have shown that education can shift consumer behaviour, but only if people are willing to confront the uncomfortable realities behind the ads and cute photos.

2. Industry and political pushback

Public demand isn’t the only reason puppy mills persist. Behind the scenes, industry lobbying and political hesitation play a powerful role.

In the US, the American Kennel Club (AKC) has repeatedly opposed stronger breeding regulations, including the Puppy Protection Act, while branding itself as a champion of responsible dog ownership.

A large portion of the AKC’s funding comes from dog registrations and breeder events, creating a clear financial incentive to resist reforms that would limit or regulate breeding.

In the UK, the Kennel Club also earns income from breed registrations, dog shows, and breeder schemes. While it promotes welfare guidance and has supported initiatives like Puppy Awareness Week, it has also been criticised for defending breed standards that contribute to severe health problems.

Critics argue that its reluctance to reform these standards enables harmful practices to continue under the banner of tradition and prestige.

Across the EU, as we explored earlier, recent reform proposals aim to introduce greater oversight and traceability. But even if those rules are adopted, their effectiveness will depend on how they’re implemented across different countries – and that’s where the political dynamics become even more complicated.

Each EU member state has its own laws, enforcement capacity, and cultural attitudes toward dogs. These differences can make negotiation difficult and meaningful oversight uneven. For example, while some countries prioritise community care, neuter-and-release programmes, and adoption, others still rely on culling or long-term detention of stray dogs.

These variations reflect how dogs are viewed, either as individuals deserving protection or as problems to be managed. A worldview that treats dogs as disposable allows puppy mills to persist and makes meaningful reform difficult to achieve.

It’s not easy to confront the fact that something as joyful as getting a puppy can be linked to suffering. But once we know the truth, we carry a responsibility to do better.

Here are some starting points:

If 1.2 million individuals (and remember, that’s just in the US, not worldwide!) are killed each year because they’re unwanted, is it right to bring even more dogs into the world?

Some argue that ethical breeding can support health and temperament, but the reality is that every bred litter potentially displaces a dog in need of a home and keeps the broader trade alive. If we want to reduce harm, we need to ask difficult questions about the necessity of breeding at all.

Justice for dogs can’t be separated from justice for all animals.

Puppy mills are just one symptom of a much wider issue: the human belief that we can breed, buy, and control other lives for our own ends. Regardless of species, the root problem is the same, a worldview that places human desires above non-human rights.

Domestication itself raises complex questions. Many dogs today exist only because we created them through generations of selective breeding, often with little regard for their physical or emotional needs. As we move toward a more ethical future, we must ask what kind of relationships we want to have with our animal kin, and what responsibilities we carry.

Dogspiracy may shock and upset people, but if it opens our eyes to what’s happening, and what’s possible, then it’s done its job.

Let’s not look away. Let’s speak up, act, and be the best friends and guardians that dogs and other animals deserve.